In the last installment, I introduced a study done by Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman that explored two key approaches to performance management—pulling and pushing. Here’s how they introduced the concepts:

When you see a task that needs to be accomplished by your team, do you “push” them to get it done or do you “pull” them in, giving them a say in how they carry it out and using inspiration and motivation to get them going? These are two very different approaches to reach a goal, and the latter is often the best one, but knowing how to combine these two paths is an important skill for managers and leaders.

Here’s the important point they made:

…knowing how to combine these two paths is an important skill for managers and leaders.

Defining the Terms

I’m going to use the definitions that Zenger and Folkman provide…

PUSHING means “driving for results.” It involves giving direction, telling people what to do, establishing a deadline, and generally holding others accountable. It is on the “authoritarian” end of the leadership style spectrum.

PULLING means “inspiring and motivating others.” It involves describing to a direct report a needed task, explaining the underlying reason for it, seeing what ideas they might have on how to best accomplish it, and asking if they are willing to take it on. The leader can further enhance the pull by describing what this project might do for the employee’s development. Ideally, the leader’s energy and enthusiasm for the goal are contagious.

The Key Take-Away

Here’s what Zenger and Folkman discovered:

While our data is clear that most leaders could benefit from improving their ability to pull or inspire others, our research revealed that leaders who were effective at both pushing and pulling were ultimately the most effective.

Once again, effective leadership style was shown to be highly situational in nature!

Here’s how they put it:

…your influence as a leader comes from your ability to know when to use which approach, depending on the task, the timing, and the people.

So…this begs the obvious question:

How do you know when to use which approach????

To help answer that question, I presented a management model in the last issue that I call, Can They? / Will They?

In this issue, I am going to present a second model I call, The Leadership Style Continuum.

Model #2 – The Leadership Style Continuum

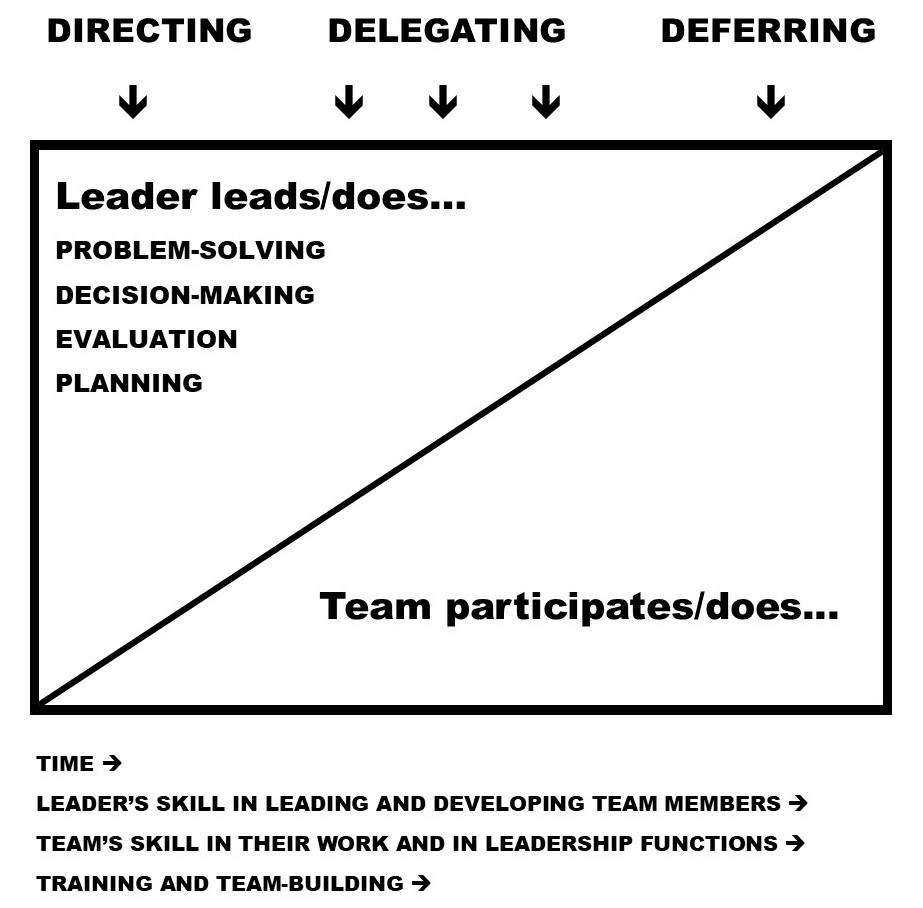

This model presents three broadly defined leadership styles (or “approaches to management”) on a continuum defined by a variety of situational elements. Here’s a diagram that will help illustrate the model:

The three main leadership styles in the diagram are…

Directing—often called autocratic

Delegating—sometimes referred to as democratic

Deferring—in the extreme, referred to as laissez-faire

The diagram is meant to illustrate how much the manager and the team members participate in the broad-based leadership processes of planning, evaluation, problem-solving and decision-making—in particular, how their participation differs with each of the three main leadership styles.

The diagram indicates the following…

1. The styles exist on a continuum. To be more specific, the distinctions between the styles are not sharply defined. The lines between styles are blurry and can blend gradually from one into another, depending on the details of a given situation.

2. As you move from left to right on the diagram, the spaces in each of the two categories (what the “leader does” and what the “team participates/does”) show increasingly lesser involvement on the part of the manager in the leadership functions and greater involvement on the part of the subordinate in the leadership functions.

3. The Directing leadership style illustrates what Zenger and Folkman would describe as pushing—“giving direction, telling people what to do, establishing a deadline, and generally holding others accountable.” It shows that the manager is the one doing all or most of the planning, evaluation, problem-solving, and decision-making.

4. The Deferring leadership style illustrates what Zenger and Folkman would describe as pulling—“describing to a direct report a needed task, explaining the underlying reason for it, seeing what ideas they might have on how to best accomplish it, and asking if they are willing to take it on.” The diagram shows that the leader is deferring to the subordinate, allowing them to take on the major responsibilities of planning, evaluating, problem-solving, and decision-making. And in extreme cases (e.g. “laissez-faire”) allowing the subordinate to take initiative with little or no input or direction from the leader/boss.

5. Somewhere in-between the two extremes is the Delegating leadership style that illustrates a manager and a subordinate sharing input and participation in the four leadership functions. Zenger and Folkman would probably identify this style as combining the two elements of pulling and pushing. NOTE: This diagram illustrates a continuum, so how much participation is involved by each party can vary quite a bit. And it can change gradually, over time.

6. The diagram also shows what is required to move from left to right, and what also limits movement in that direction—toward greater subordinate participation:

…The level of skill that team members have (a) in their particular work; and (b) in the four leadership functions. As the skill of a team member develops, they are able to more effectively participate in planning their work; evaluating their work; solving problems in their work; and making decisions about their work. Also, as they develop skill in the leadership functions, they are able to more effectively participate in each one (e.g. as they develop better problem-solving skills, they are able to more effectively participate in problem-solving activities).

…The level of skill that the leader has (a) to lead and manage; and (b) to coach and develop team members. Obviously, the more adept a manager is at training and coaching subordinates, the more likely those direct reports will be able to learn, grow, and participate more effectively in the leadership functions listed.

…Training and team-building activities. Teams (and individual team members) function more effectively if (a) they receive training in how to function as a team; and (b) spend time exercising and developing their collaborative team-building skills.

…Time. All of the above require an expenditure of time. Individual growth and team development do not occur instantaneously. Expecting otherwise is unrealistic and disheartening for both a manager AND their subordinates.

These four variables give managers a practical framework for evaluating each situation, to help them determine how much pushing or pulling is required in each particular assignment. Having said that, managing is still very much an art as much as it is a science—it requires a leader to develop skill, good instincts, and a realistic understanding of each of their subordinates—sufficient to inform effective management decisions in each situation, with each person, and each task involved.

And if you would like help with your unique management challenges, leave a comment and your contact information…and help will be on the way!

Until next time… Yours for better leaders and better organizations,

Dr. Jim Dyke – “The Boss Doctor” ™ helping you to BE a better boss and to HAVE a better boss!